by Danila Bochkarev

In December 2025, the EU agreed on a ban on all Russian gas imports by the end of 2027, with the legislation expected to enter into force in January 2026. Whether or not this law will be challenged by dissatisfied member states such as Hungary or Slovakia, it will have a significant impact on the European gas market. In any case, it is likely to increase interest in importing additional pipeline gas from alternative sources.

The EU already imports pipeline gas from Norway, North Africa, and Azerbaijan, while the expanding wave of LNG supply is expected to further depress spot prices across the continent. One early signal of this trend has been the narrowing spread between TTF and Henry Hub prices, with TTF falling below the long-run marginal cost of U.S. LNG exports. As IEA’s Greg Molnar notes, the “TTF–Henry Hub spread is expected to tighten in a structural manner.” While abundant LNG supply is likely to keep prices relatively low, it does not necessarily guarantee price stability. LNG-dominated markets remain vulnerable to sharp price fluctuations, in contrast to regions with more diversified gas supply portfolios. The United States provides a relevant example. In New England, limited pipeline capacity has repeatedly caused severe price spikes when infrastructure constraints bind, particularly during cold weather. According to Argus, New England spot gas prices averaged $21.51/MMBtu (approximately $720 per 1,000 cubic meters) during the first week of December. This level was significantly higher than delivered LNG prices in northwest Europe, where January delivery traded at $8.70/MMBtu (approximately $300 per 1,000 cubic meters) on 8 December. Although the EU gas market is more complex than that of New England, the addition of further pipeline supply sources should enhance market liquidity and help mitigate extreme price volatility over time.

At present, the Caspian region is the best available source of additional pipeline gas for Europe if the EU proceeds with a total ban on Russian gas imports. Azerbaijan is already the key supplier of pipeline gas from the region to the EU, with just under 13 bcm delivered in 2024. European companies are also seeking to expand their portfolios of Azerbaijani gas. In June 2025, Bloomberg reported that Germany’s SEFE signed a 10-year agreement with Azerbaijan’s SOCAR to purchase 1.5 bcm per year, with deliveries starting this year. Hungary has followed suit at the government level. In December, Budapest signed a framework agreement with Baku to buy 0.8 bcm over two years. Azerbaijan may be able to offer additional export volumes, but not in the near term, and any incremental supplies are likely to be limited. Iran has a theoretical potential to become a large-scale exporter of pipeline gas. However, this would require substantial investment in upstream capacity and, more importantly, the lifting of international sanctions on Tehran. Even gas exports to neighbouring Pakistan are currently stalled due to geopolitical factors, despite much of the necessary infrastructure being in place. As a result, Iran remains effectively out of the picture for now. This leaves Turkmenistan as the only significant potential addition to Azerbaijani gas in the region that could, in principle, be available for export to Europe.

Turkmenistan has very large natural gas reserves, currently estimated by both Cedigaz and international energy companies at up to 13–14 tcm. Production costs in Turkmenistan are relatively low, potentially below USD 30 per 1,000 cubic metres. Despite some technical constraints, Ashgabat has scope to ramp up gas production, as current output levels remain well below those reached in the late Soviet period. Regional infrastructure could also be expanded to accommodate additional gas flows from the Caspian to the EU. The Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) is designed to reach up to 20 bcm per year, while TANAP could be expanded from 16 bcm per year to around 31 bcm per year.

There are two main options for bringing Turkmen gas to Europe: via a trans-Caspian link or through swap arrangements with Iran.

The first option – a limited-capacity interconnector between the gas systems of Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan has been discussed for many years, with renewed interest more recently. Following the sharp reduction in Russian gas supplies to Europe, the political concept of a trans-Caspian pipeline has re-emerged. In 2018, the leaders of the Caspian littoral states signed the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea. The convention confirmed that the construction of subsea pipelines requires “agreement only between the countries through whose sectors the pipeline passes”. In principle, this removed a key legal obstacle and should facilitate new projects such as the Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP), at least in a limited form, for example a 10 bcm per year interconnector linking the Azerbaijani and Turkmen pipeline systems. The question remains whether environmental challenges and regional geopolitical tensions will allow for the fast and smooth realization of this route.

A second option involves swap agreements. In theory, Turkmenistan could export up to 20 bcm per year to Azerbaijan, Turkey, Europe, and Iraq through existing pipeline connections with Iran. Turkmenistan has already relied on swap arrangements with Iran to diversify its pipeline gas exports. In 2023, Azerbaijan imported 1.51 bcm of Turkmen gas via Iran. Turkmenistan also signed a gas supply contract with Turkey to deliver up to 1.3 bcma through Iran. However, supply volumes have remained modest and volatile. In the first half of 2025, Azerbaijan imported only 0.187 bcm of Turkmen gas. Deliveries began in March 2025, and between March and June 2025 Turkey imported approximately 0.46 bcma, before the flows abruptly ceased. Oilprice.com identified new U.S. and EU sanctions against Iran, introduced in June and September 2025, respectively, as the main reasons behind the reduction in gas flows. These fluctuations in flows highlight the existing challenges. Sanctions against Iran or renewed regional tensions could therefore disrupt, or even bring an end to, swap agreements at any point.

Furthermore, a challenge common to both options is the cost of delivering gas to European markets, combined with EU policies that discourage the conclusion of new long-term contracts and large-scale investment in new gas infrastructure in line with decarbonization objectives. The cost of transporting gas from the Caspian region to the EU border or the Italian market, estimated at $40–50/mcm via the South Caucasus Pipeline (SCP), $107/mcm via TANAP, and $65/mcm via TAP, already places a significant burden on project economics. In addition, transit through Iran, which according to unverified sources could amount to up to 15% of the gas price, or alternatively the operational costs associated with a Trans-Caspian link, would further erode margins. As a result, profitability for Turkmenistan would remain limited, even if transit costs decline following potential expansions of the TAP and TANAP pipelines.

Additionally, any change in the geopolitical environment could at least partially reopen the door to strong competitors such as Iran or even Russia. Any sustainable peace deal is likely to include gas supplies to Ukraine, which, even if only a small part of these volumes ends up in the EU, would reduce Ukraine’s imports from Europe and therefore lower overall EU demand for imported gas. In the event of sanctions relief, Iranian gas could readily gain access to the TANAP pipeline. In this context, the best-case outcome would be at most 10 bcm per year of Turkmen gas flowing to Turkey and significantly smaller volumes reaching Europe.

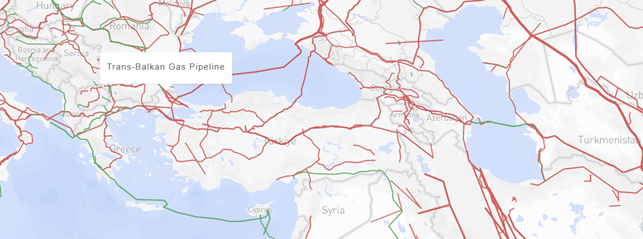

Map 1 Existing (in red) and planned (in green) gas pipeline infrastructure linking the Caspian region and Europe. Map of the region is adapted from Global Gas Infrastructure Tracker, Global Energy Monitor, November 2025 ©. All Global Energy Monitor tracker data are freely available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License

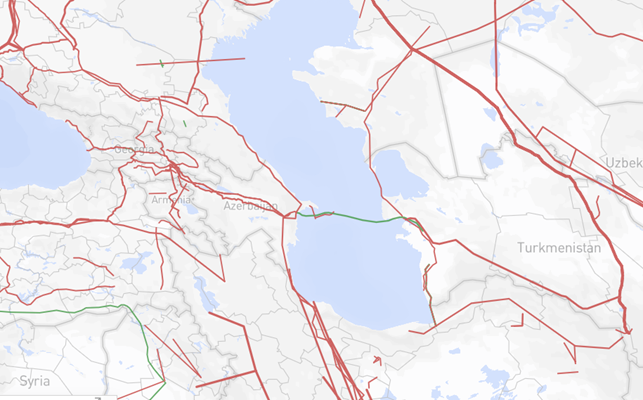

Map 2 Existing (in red) and planned (in green) gas pipeline infrastructure in the Caspian region. Map of the region is adapted from Global Gas Infrastructure Tracker, Global Energy Monitor, November 2025 ©. All Global Energy Monitor tracker data are freely available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License