By Irina Mironova for Cedigaz

Israel’s natural gas sector is increasingly discussed in the context of global LNG markets. Having moved from energy self-sufficiency to sustained export capability, Israel now influences the LNG system indirectly, through its integration with Egypt’s gas and power balance. The relevance of Israeli gas therefore lies in how gas is allocated under stress: as regional balances tighten and security risks rise, Israeli pipeline flows shape the margin between power stability and availability of feedgas for LNG in Egypt.

Israel’s gas sector: from domestic security to regional anchor

For most of the past decade, Israel’s natural gas policy was framed almost entirely around domestic security of supply. The development of Tamar, followed by Leviathan, was driven by the need to displace coal in power generation, reduce exposure to imported fuels, and stabilise electricity prices. Export options existed, but they remained politically sensitive and clearly secondary to domestic priorities.

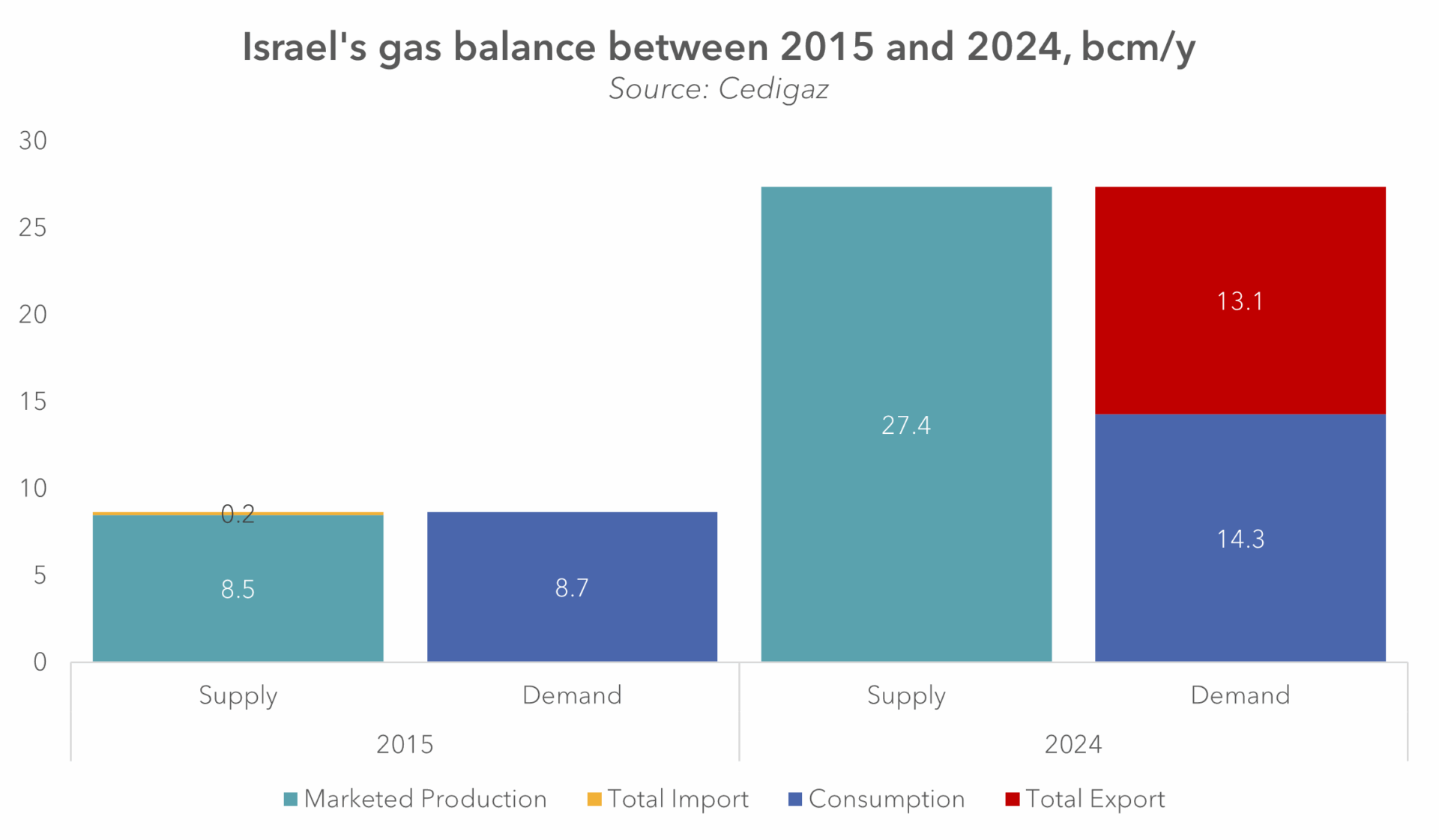

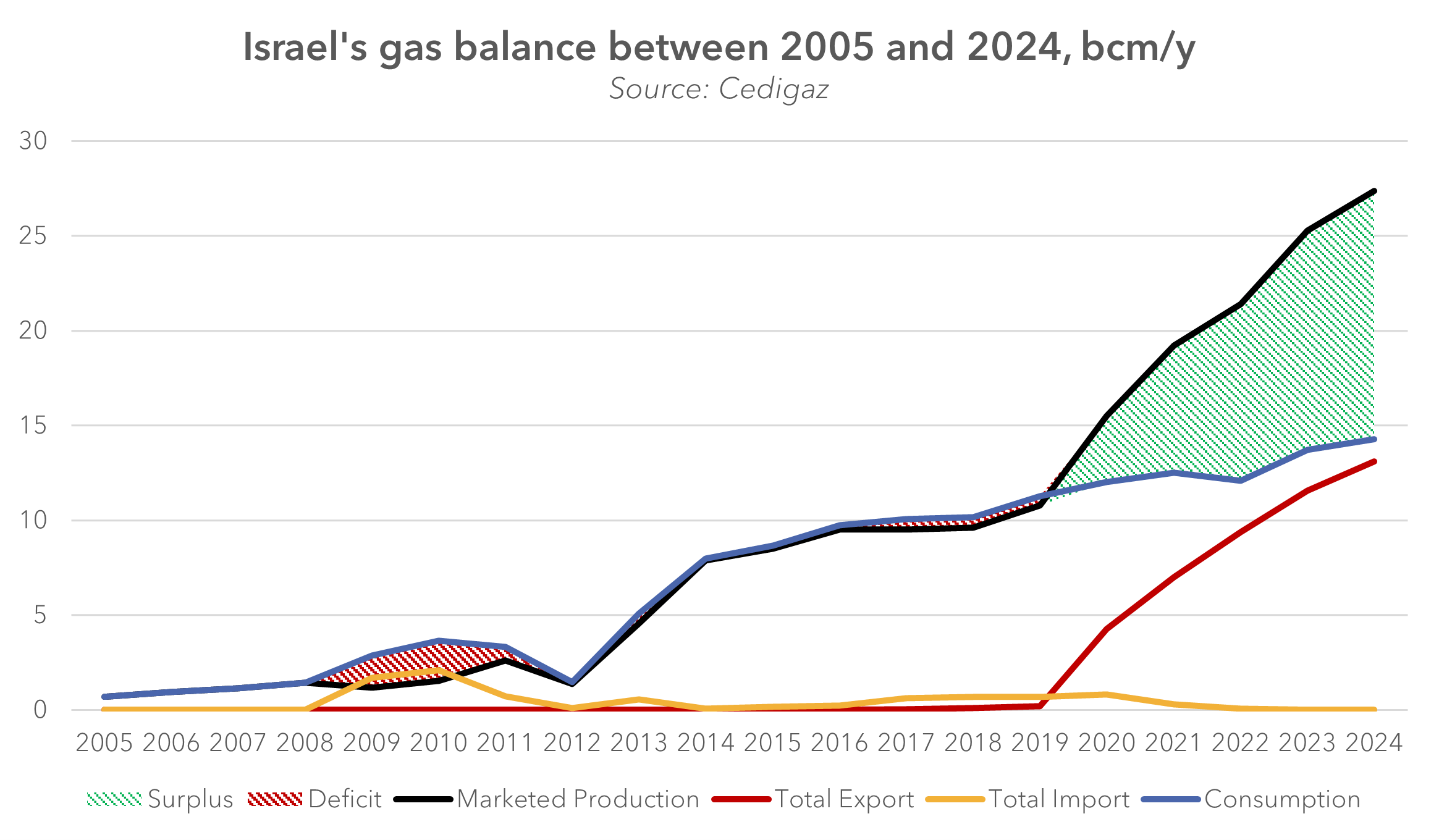

That balance has now shifted. With domestic demand fully met by existing production, Israel operates a structural gas surplus relative to internal consumption.

While modest by global standards (around 13 bcm in 2024) this surplus is predictable and expanding. More importantly, it is underpinned by an institutional framework that explicitly prioritises domestic needs. Export permits, transmission arrangements, and upstream development plans are designed to preserve this hierarchy.

While modest by global standards (around 13 bcm in 2024) this surplus is predictable and expanding. More importantly, it is underpinned by an institutional framework that explicitly prioritises domestic needs. Export permits, transmission arrangements, and upstream development plans are designed to preserve this hierarchy.

The final investment decision on the expansion of Leviathan and the allocation of capacity on the planned Israel–Egypt Nitzana pipeline consolidate Israel’s role as a regional source, capable of increasing deliveries to neighbouring markets (existing pipeline connections allow direct exports to Egypt and Jordan; the recent developments were centred on Egyptian exports).

Israel’s advantage in this configuration lies not in scale, but in control over allocation. Gas flows can be redirected between domestic demand and regional exports as conditions change. In June 2025, for example, during the escalation of hostilities between Israel and Iran, the Energy Ministry ordered a temporary shutdown of Leviathan and Karish fields (Tamar continued to supply the domestic market; production and exports resumed in late June 2025). The decision had immediate knock-on effects for Egyptian gas balance.

This capacity to absorb shocks internally while remaining outward-facing marks a qualitative shift in Israel’s gas role. It is under these conditions, defined by surplus, institutional control, and flexible allocation, that Israeli gas begins to matter beyond domestic security of supply and acquires regional significance.

Egypt: where Israeli gas meets the LNG system

Once Israeli gas enters Egypt’s system, it becomes part of a tightly managed domestic balance, where allocation decisions are driven by immediate system stability.

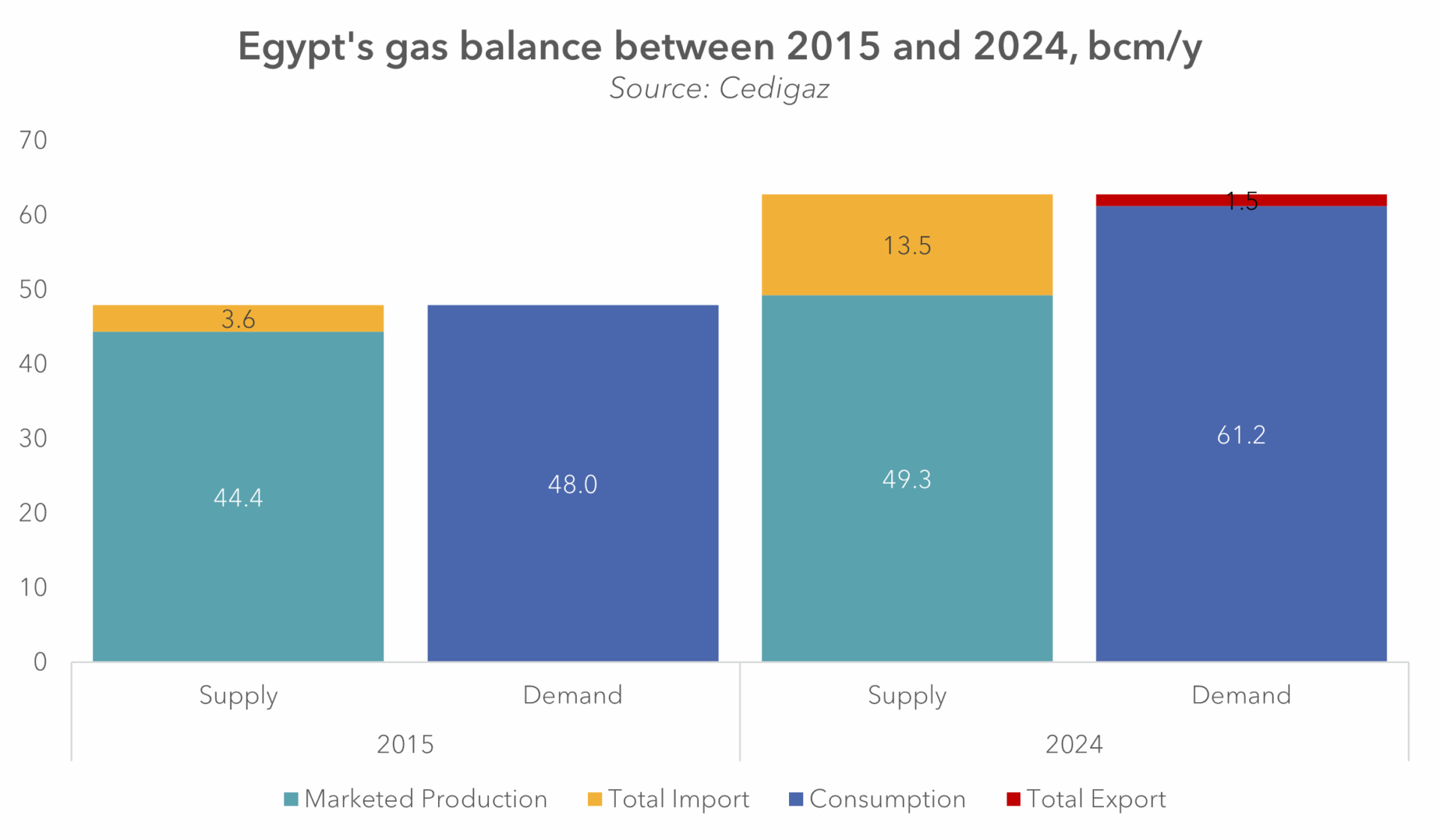

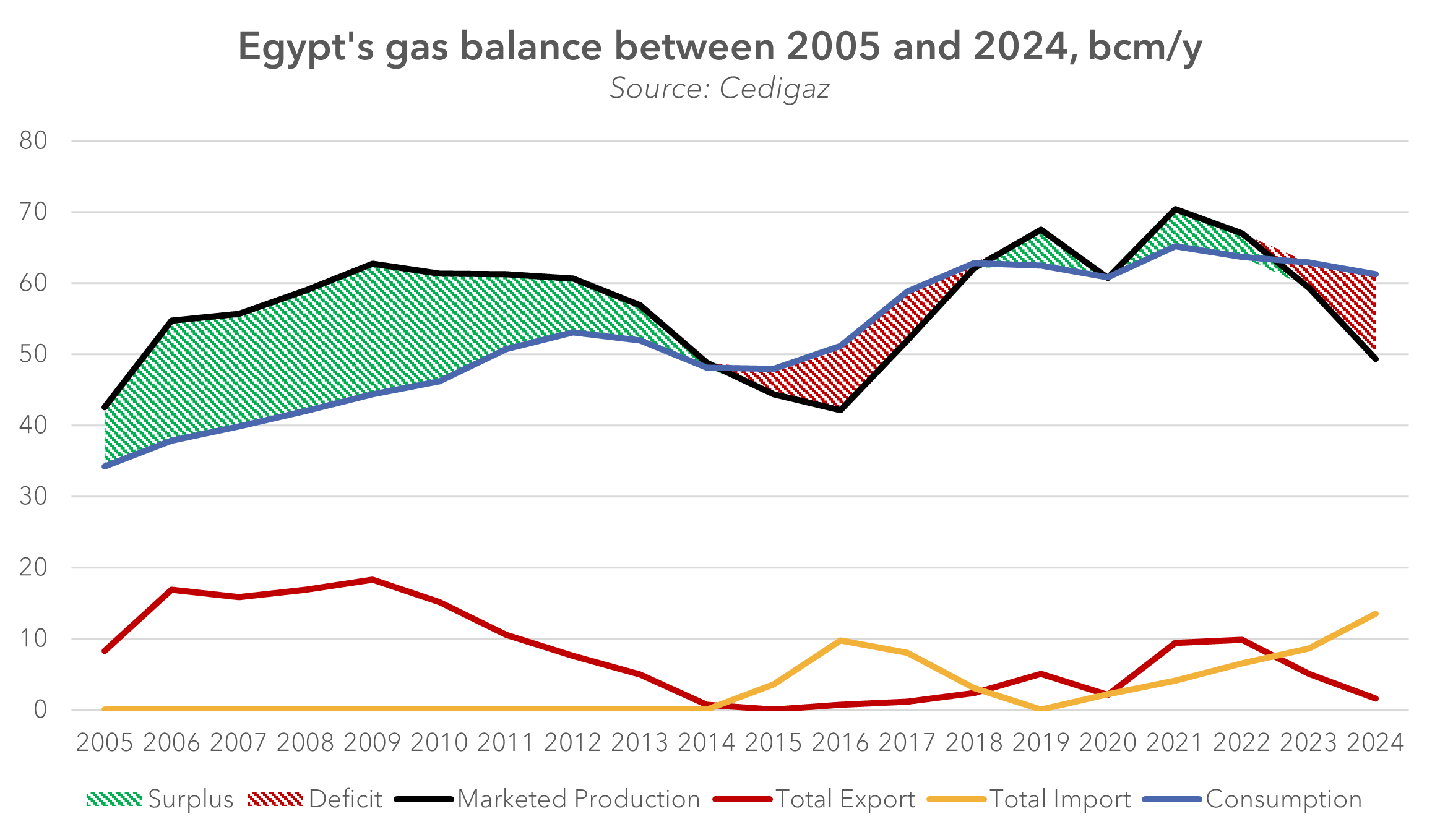

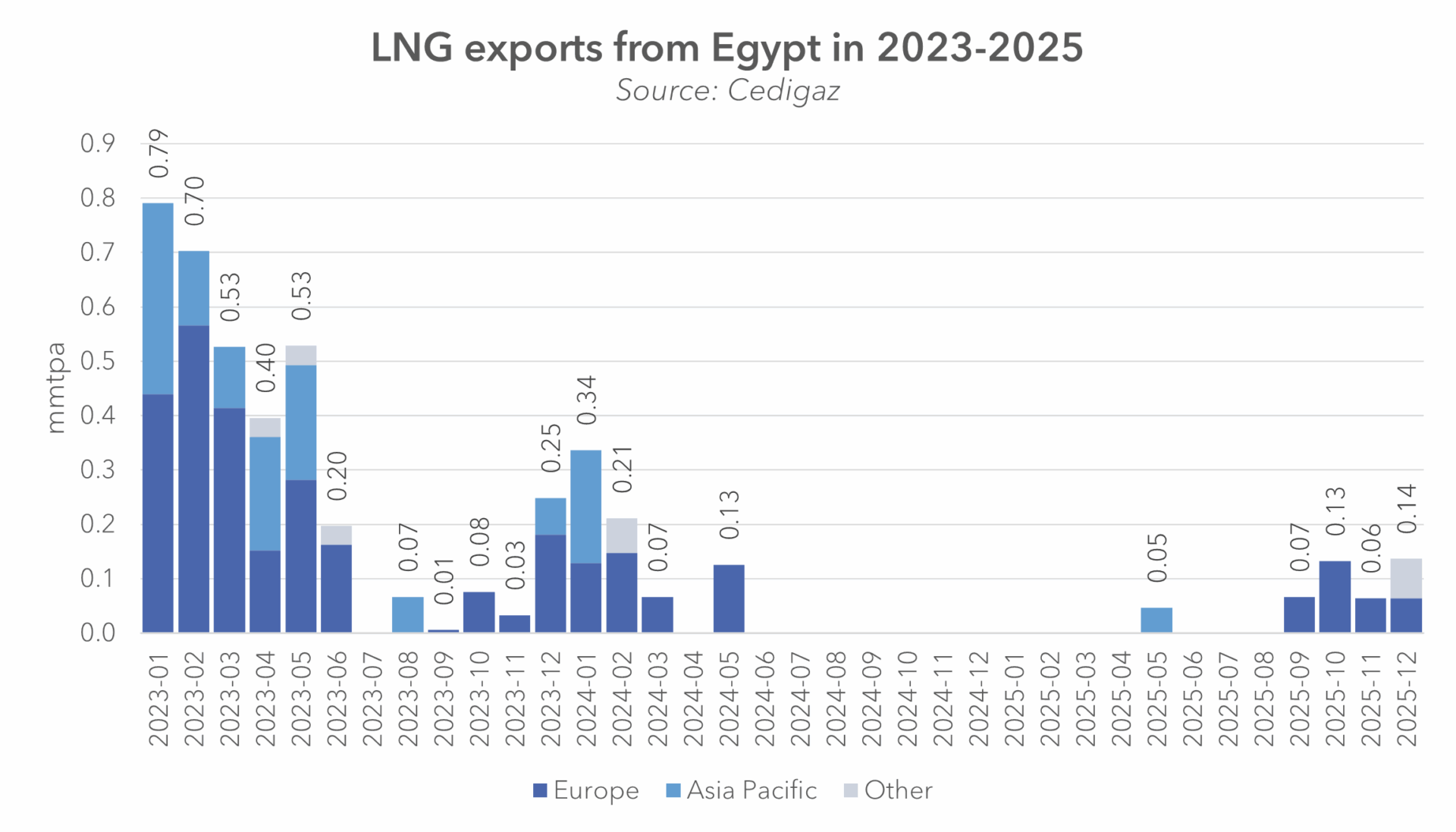

Over the past two years, Egypt’s gas balance has come under sustained pressure. Declining output from mature offshore fields has coincided with structurally rising power-sector demand, particularly during peak summer months. As a result, gas availability has increasingly proven insufficient to meet electricity generation, industrial demand, and LNG liquefaction on a continuous basis.

In this environment, the system reverts to explicit prioritisation. Gas supply to the power sector, which dominates Egypt’s gas demand, takes precedence. LNG feedgas is treated as residual. The repeated curtailments and temporary shutdowns at Idku and Damietta in 2023–2024 were therefore not operational anomalies or isolated incidents, but the predictable outcome of this dispatch logic under stress.

Gas imports have taken on a growing balancing role.

Since 2024, Egypt has also re-emerged as a net importer of LNG. This trend is set to extend into the medium term, with QatarEnergy having agreed to supply up to 24 LNG cargoes to Egypt during the summer of 2026 to support peak-season power demand.

Since 2024, Egypt has also re-emerged as a net importer of LNG. This trend is set to extend into the medium term, with QatarEnergy having agreed to supply up to 24 LNG cargoes to Egypt during the summer of 2026 to support peak-season power demand.

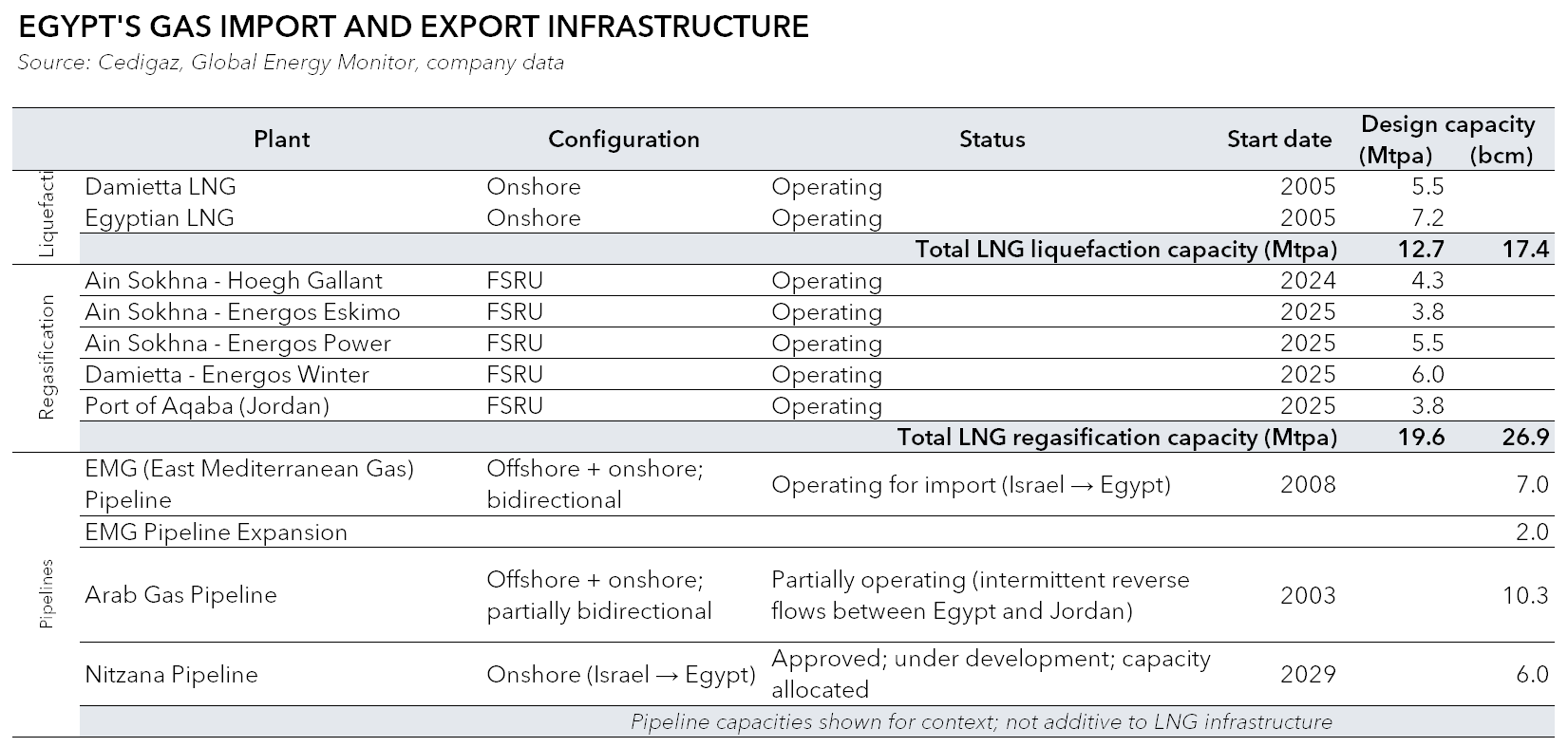

Egypt’s balancing is enabled by a diversified import infrastructure that combines cross-border pipelines with floating regasification capacity at own ports, as well as access to the Aqaba terminal in Jordan.

While both the EMG pipeline and the Arab Gas Pipeline were originally designed to support Egyptian gas exports, their current functions differ markedly. EMG now operates as a dedicated import route for Israeli gas into Egypt and is set to be expanded following recent upstream investment decisions in Israel.

While both the EMG pipeline and the Arab Gas Pipeline were originally designed to support Egyptian gas exports, their current functions differ markedly. EMG now operates as a dedicated import route for Israeli gas into Egypt and is set to be expanded following recent upstream investment decisions in Israel.

The Arab Gas Pipeline remains only partly operational, with several segments idle, and while it is predominantly used for exports, it has occasionally operated in reverse, allowing regasified LNG from Aqaba to flow into Egypt.

If the planned EMG expansion and the Nitzana pipeline are realised, Israel’s pipeline supply capacity to Egypt could reach around 15 bcm per year. These flows help narrow Egypt’s supply–demand gap and reduce the frequency and severity of power-sector shortfalls. However, they do not convert into firm, baseload export LNG supply. Liquefaction remains interruptible, sensitive to domestic demand swings, and vulnerable to both balance tightening and external disruptions.

The implications extend beyond large-scale LNG exports. Potential bunkering services along the Suez corridor and other LNG-dependent activities inherit the same volatility.

The implications extend beyond large-scale LNG exports. Potential bunkering services along the Suez corridor and other LNG-dependent activities inherit the same volatility.

Asymmetry and leverage: why this interdependence works

The Israel–Egypt gas relationship in fact increases regional stability by concentrating it asymmetrically. The consequences of disruption are unevenly distributed, shaping incentives on both sides.

For Israel, gas exports are structurally optional. Volumes can be redirected or curtailed without destabilising the internal power system or forcing emergency imports. This flexibility limits Israel’s exposure to short-term shocks and preserves policy autonomy under stress.

For Egypt, the exposure is materially different. Gas shortfalls translate directly into pressure on the electricity grid, public finances, and ultimately social stability. Power-sector disruptions carry immediate political costs, while LNG curtailments, though economically significant, are secondary in the hierarchy of risks.

As a result, Egypt bears the greater downside from any sustained interruption in pipeline gas flows. Infrastructure specificity reinforces this asymmetry. Moreover, public disclosures suggest that at least part of Israeli gas export agreements with Egypt is structured around large aggregate volumes delivered over time, rather than fixed annual offtake commitments. The emphasis on total volumes, phased increments, and infrastructure-linked timing indicates a preference for flexible delivery profiles that preserve domestic supply optionality.

Gas as a stabiliser, LNG as a variable

Taken together, the system points to a clear hierarchy. Israeli gas contributes to regional stability primarily by supporting Egypt’s electricity system, where continuity of supply carries immediate economic and political weight. LNG exports follow from this stabilisation, but they are neither automatic nor assured. They emerge only when domestic balances allow and retreat when the system is under stress. For global LNG markets, this means that Egyptian cargoes should be understood as structurally interruptible supply, valuable at the margin, but unsuited to baseload assumptions.

LNG is often presented as the most flexible form of gas trade, while pipelines are treated as rigid, path-dependent infrastructure. The Israel–Egypt case challenges this assumption. For Israel, pipeline exports offer greater operational and political flexibility than liquefaction would: volumes can be scaled up or curtailed quickly, redirected between domestic demand and regional markets, and adjusted under security stress without breaching long-term LNG delivery commitments. By contrast, LNG would lock gas into fixed export schedules, concentrate security risk in immobile assets, and reduce Israel’s ability to reallocate supply when conditions change. The key takeaway for market participants is that flexibility is not an inherent property of LNG versus pipelines, but of how infrastructure interacts with domestic priorities, security constraints, and system governance.