By Irina Mironova for Cedigaz

Pakistan’s LNG market developments in 2025 offer an illustration of how demand assumptions can shift in emerging Asian import markets. A combination of weakening gas demand, rising renewable generation and rigid long-term contractual commitments has forced an adjustment of LNG intake through cargo cancellations, diversions and resale arrangements. Pakistan’s experience highlights the growing importance of demand risk, contractual flexibility and portfolio management in markets where structural change is increasingly shaping gas consumption.

Over recent months, Pakistan has featured repeatedly in LNG-related news flow.

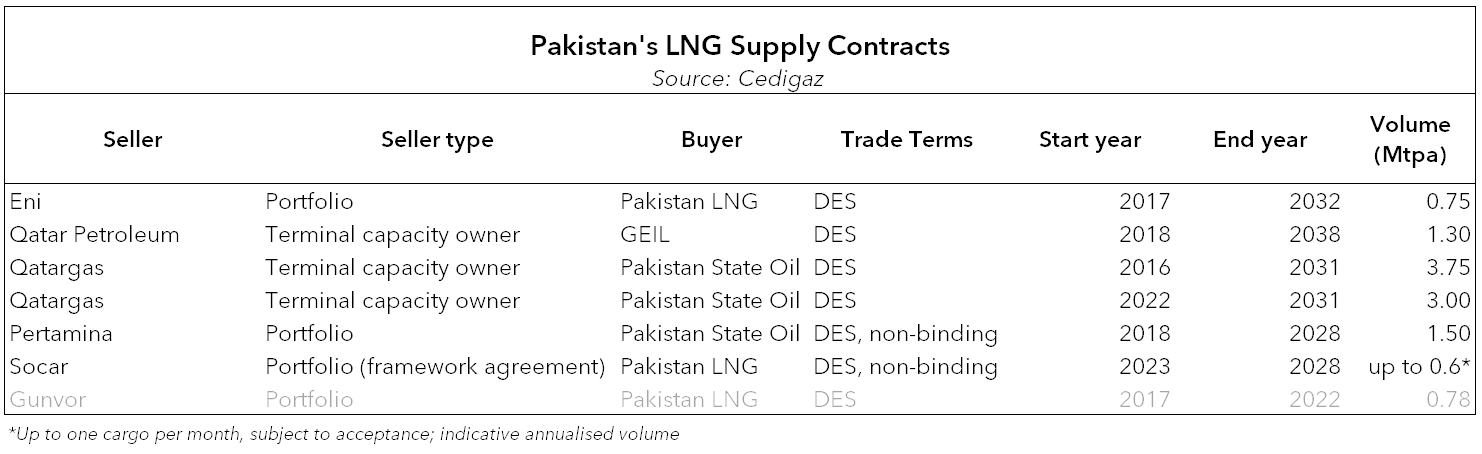

- Nov 4, 2025 – Pakistan cancels 21 Eni cargoes for 2026–27, retains only deliveries aligned with peak system demand; discusses resale/deferral options.

- Nov 14, 2025 – Pakistan and Qatar agree to divert 24 cargoes in 2026 under net-proceeds logic.

- Dec 1, 2025 – Pakistan approves 2026 Annual Delivery Plan enabling diversion of 35 long-term cargoes by QatarEnergy and Eni; clarifies application of a non-performance delivery clause and price-risk sharing with PSO.

- Dec 8, 2025 – Pakistan confirms plans to sell surplus LNG cargoes on international markets from Jan 2026; oversupply persists; LNG-to-power down.

Why Pakistan matters

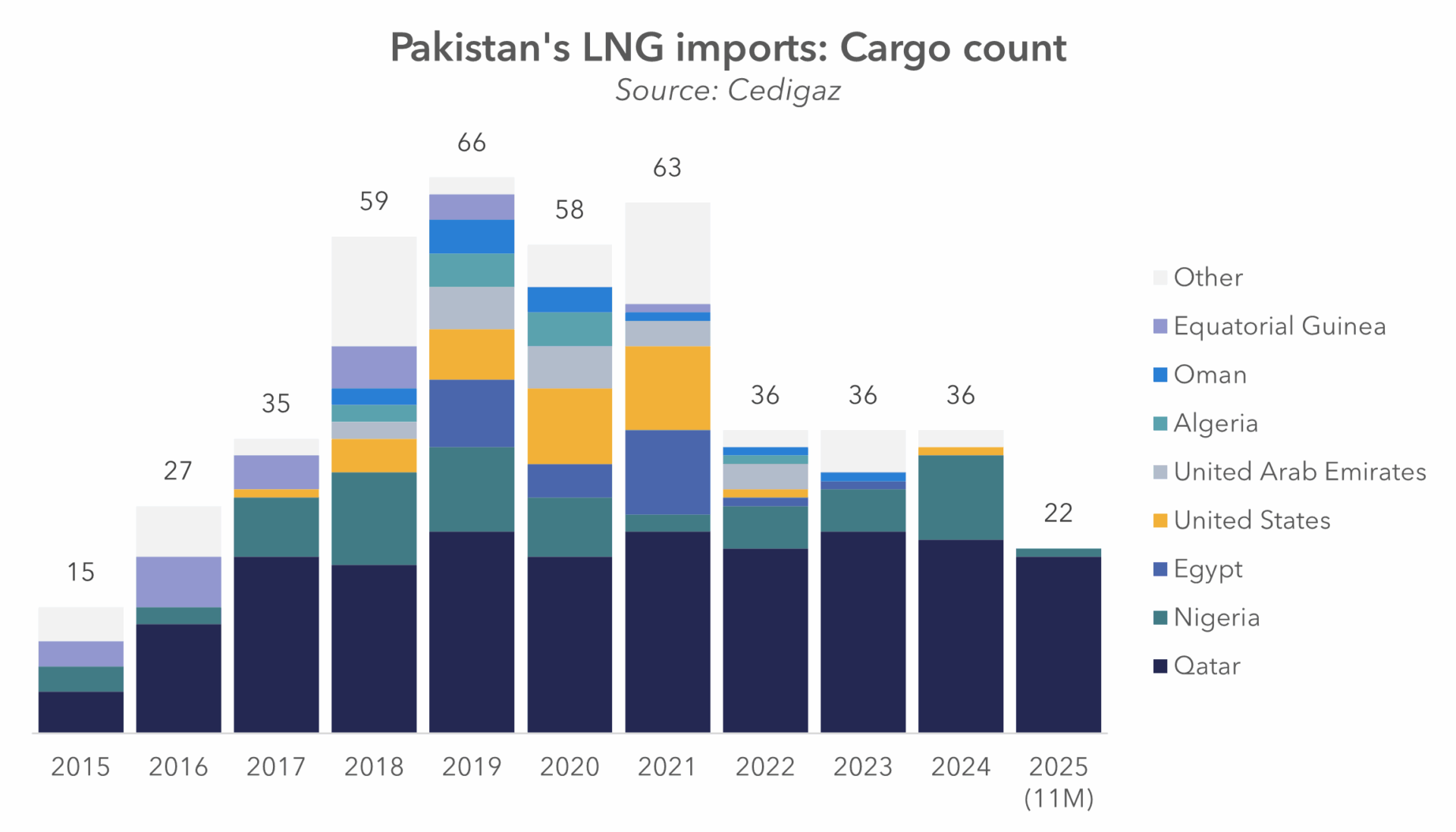

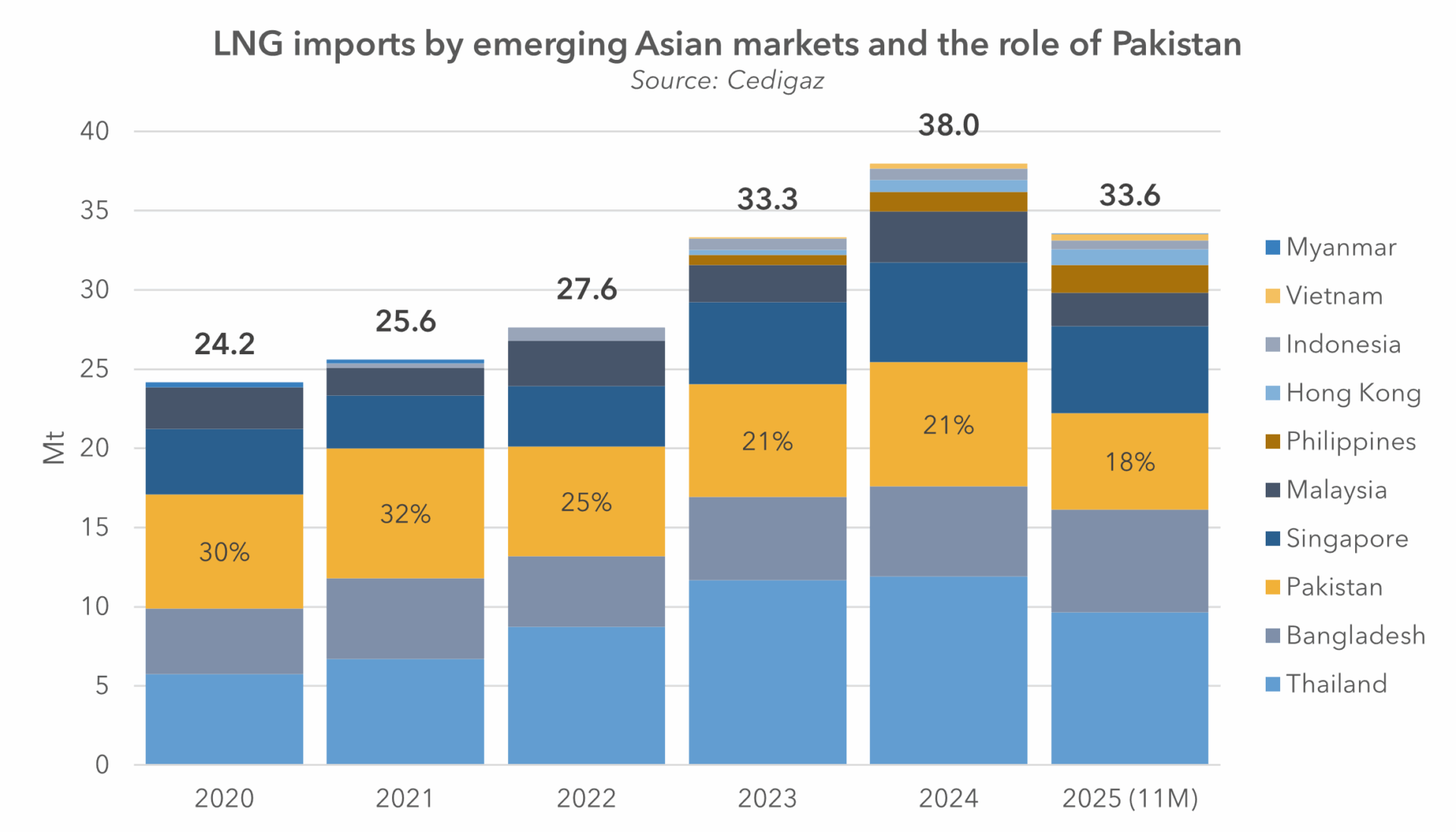

The country is commonly grouped among emerging Asian LNG markets[1] and has long been one of the largest contributors within this group. In recent years, however, both import volumes and relative market share have declined, with LNG imports falling from 8.2 Mt in 2021 to 7.2 Mt in 2023 and reaching 6.1 Mt in the first eleven months of 2025. Pakistan’s share of the group’s imports declined from around 30% in 2020 to approximately 18% in 2025. It also shifted from 2nd to 3rd place within the group, overtaken by Bangladesh in 2025.

The IEA’s World Energy Outlook (2025) frames LNG demand growth in emerging Asian markets as primarily a replacement fuel for declining domestic gas production, with the sca

le of uptake critically dependent on price levels, infrastructure availability, and system flexibility. Pakistan fits this category in principle: it has mature and declining domestic gas production, .

Pakistan’s reorientation away from gas and LNG in the power sector was actually embedded in official planning documents by 2020. The Indicative Generation Capacity Expansion Plan 2047 (IGCEP) explicitly projected a declining role for gas and LNG in favour of coal and renewables. The main rationale was to reduce dependence on imported fuels in the power sector from nearly 50% to below 2% by 2047, driven by growth in indigenous coal and hydropower plus other renewables.

The IEEFA’s Rising LNG Dependence in Pakistan report (2022) also described LNG imports as a response to declining domestic gas production and chronic supply shortfalls, but cautioned that LNG was being absorbed into a downstream system characterised by non-cost-reflective tariffs, fiscal stress and limited demand elasticity. By 2022, LNG was therefore positioned as a marginal and balancing fuel rather than a baseload anchor, with exposure to price volatility and take-or-pay risk embedded from the outset.

LNG system and contract landscape

Pakistan’s current standing in the LNG sector reflects a system that is technically capable of absorbing LNG volumes but increasingly constrained on the demand side.

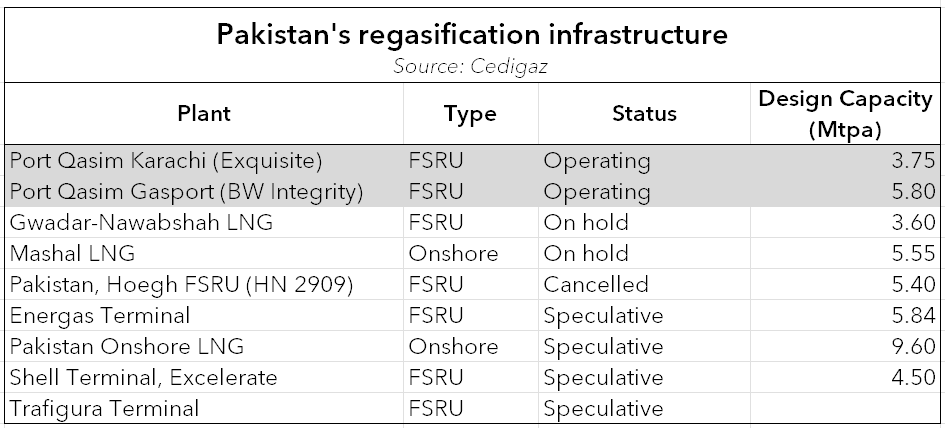

From a physical perspective, the country has established LNG import and regasification infrastructure, including terminal capacity that provides the technical ability to receive and process around 9.5 Mtpa of LNG.

On the demand side, LNG use in Pakistan has been structurally linked to power generation. In FY 2017–2018, around 65% of imported LNG was consumed by the power sector. Data from Pakistan’s Central Power Purchasing Agency cited by Argus indicate that gas sourced from imported LNG accounted for around 17% of total power generation in January–August 2025, down from an average of approximately 20% over the 2020–2023 period. Higher relative fuel costs have pushed LNG-fired generation lower in the power grid merit order in 2025, encouraging greater use of coal-fired plants and renewable power sources in place of LNG. Industrial demand has also weakened, as many consumers have shifted toward captive and self-generation solutions. As a result, LNG is increasingly used as a seasonal or balancing fuel rather than a baseload supply source, reducing the system’s ability to absorb contracted volumes year-round.

Pakistan’s LNG supply portfolio is dominated by long-term, binding DES SPAs, with QatarEnergy/Qatargas and Eni accounting for the majority of contracted volumes recorded in the Cedigaz LNG Supply Contracts Database.

Implications

The scale of LNG cargo diversions planned for 2026 is broadly comparable to Pakistan’s total annual LNG arrivals in recent years, indicating that LNG imports may increasingly be confined to periods of peak system stress rather than serving as a stable, year-round supply source.

Notably, this compression of LNG demand reflects long-standing policy direction in addition to response to elevated price levels. LNG consumption in Pakistan has historically been concentrated in the power sectorLNG import decline was already embedded in official planning. Under the IGCEP base scenario published in 2020, the share of LNG-fired power generation was projected to decline sharply from around 23% of the power mix in 2017–2018 to around 11% by 2025, and to a negligible level by 2035. This implied a reduction in LNG demand from the power sector of roughly 1.3 Mt by 2025. While realised LNG demand in 2025 has remained higher than envisaged in the IGCEP projections, the observed direction with 2026 cargo diversion is broadly consistent with those plans.

Taken together, these developments point to a structural mismatch between contracted LNG volumes and domestic demand in Pakistan and highlight a broader pattern of structural demand erosion that may extend beyond Pakistan to other price-sensitive emerging LNG markets.

[1] For the purposes of this analysis, “emerging Asian LNG importers” refers to LNG-importing countries in Asia excluding the established large importers China, India, Japan, the Republic of Korea and Taiwan. The group therefore includes Bangladesh, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Pakistan, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.